Kim, Tobbe and Steve discuss – It’s not Who You Know It’s How you Know Who You Know.

Positives and pitfalls of Social Networking, Company perceptions and Honest Relationships.

Kim, Tobbe and Steve discuss – It’s not Who You Know It’s How you Know Who You Know.

Positives and pitfalls of Social Networking, Company perceptions and Honest Relationships.

Nowadays most of us spend most of our lives in an office type environment.

The idea of an effective work environment has always been present and yet often rarely discussed or analysed by most of us, myself included. I just know what I like and often modify my surroundings to make the best from a less than ideal situation.

The old school office/cubicles strategy, was rooted in hierarchy and even class structure. The “us and them” school of though between “management” and “labour”, yet it did allow for personal and private spaces which meant an inherent feeling of safety and ownership.

The open plan strategy, has its ideology based in the “we are a team” and “we are all the same” mindset. These ideas have issues in a work place; the bigger the team the more difficult to find harmony and we are not all the same. The funniest thing about the open plan office space is that a major reason for its popularity is not to develop an effective work environment but that its cheaper per headcount by easily fit more staff into smaller spaces and also that you can see everyone, giving the illusion of control.

The simple fact is that we often ignore or actively block out our environment be it work or otherwise. Details of our environment and how they effect our mental state, often go unnoticed and therefore are allowed to impact us without being monitored or adjusted.

How many of us remember the office spaces of our past and television sitcoms, cubicles, isolated offices and founded in the “us and them mentality”. Nowadays, we have the antithesis, being touted as the best option, the open plan, no partitions idea of office space. The driving force behind each extreme model, is only partly based in trying to allow for effective work.

The irony is that, as humans we need interactions with others and also our private space. Much like marine fish in a fish tank, I’ll get back to this later.

The traditional office space of the decades past, was one of higher management nested in largish offices around a space of partitioned cubicles. This lay out although not great had it’s merits. The physical barriers allowed the occupants to have a sense of private space and belonging. The ocean of cubicles provided a pocketed approach to office space, reminiscent of battery hens. Each isolated and working to produce, under the watchful eye of the farmer/manager.

As time and ideas changed the partitions got smaller in height and less common, the offices reduced in number and common areas began to spring up. The idea of this was to remove the barriers physically and hopefully mentally from the work space to allow for communication and a sense of community and partnership, to hopefully evolve.

The interesting fact is that different cultures behave differently but people tend to require the same things.

Ironically as the physical barriers, like walls and partitions, have been reduced or completely removed others have been erected to fill a need. The partitions have gone but the need for private spaces has meant that isolationist devices have become common place. The modern office space is open plan and headset isolated. The human need for self-space has replaced the partitioned cubicles with the modern cultural equivalent of isolation tanks.

The supposedly open office to encourage freedom and so we can have a sense of community and belonging has gone full circle to the isolationist mentality of boxes.

The mental isolation in the modern open plan work space is, far more detrimental than the cubicles of old and more difficult to see.

Personally I felt happier in cubicles, with lowish partitions and one glass partition so natural light could be allowed further into the room. The partitions were set out in blocks of four or six and sometimes even eight, allowing for team groupings and interactions.

The partition walls were low enough to see over, when you were standing but high enough to utilise them as extra work surfaces for charts and the tracking of work in progress. The sense of privacy was there and you also had a sense of belonging. You could hear others if you wished to focus or easily ignore the office murmurs.

If you have ever kept a marine aquarium or any fish tank for that matter there is a paradox which occurs when stocking your aquarium.

“The more hiding places there are the more you see your fish and the less stressed they are.”

In a marine environment fish are constantly on the look out for predators and prey alike, always aware and highly observant. The fish in a tank are no different, being exposed is stressful and a bad thing. A stark and barren environment, is a terrifying place and that is why fish kept in these conditions are rarely seen and often found cowering in what few corners or hiding spots there are. An aquarium with lots of hiding spots and ample swim throughs will make the inhabitants feel safe since they can always dart into a secluded spot, when danger is felt.

Maybe we should bare this in mind when designing work spaces.

A final thought is that traditionally homes are designed with common areas, lounge and living rooms, common rooms for eating and cooking and most importantly private zones the bedrooms.

So we all know about stakeholders…those people that care about what we are doing and should have a say in what happens.

So we all know about stakeholders…those people that care about what we are doing and should have a say in what happens.

Are there also people that care about the thing that the stakeholders care about that we would not call stakeholders?

What does the ‘stake’ mean when we refer to the stakeholder? According to Wikipedia, the term originally referred to the person who temporarily held the stakes from a wager until the outcome was determined. Business has since co-opted the term to mean people interested or impacted by the outcome of a project.

Tobbe and I were having burgers for lunch today…they were so tall that they had skewers in them to keep them together. So the chef held the skewer (stake) and we held the skewer when we ate the lunch, but the person serving us never touched the skewer…just the plate that supported the burger with the skewer in it.

That got us thinking about what supports the interests of the stakeholders, and yet, is not a stakeholder of a project or outcome?

It may be what we call governance. The scaffolding in an organisation that ensures that business interests are looked after…ensuring that our burgers arrive safely and without toppling over onto the floor.

Expanding the thoughts behind a recent tweet of mine.

‘Pondering….less obvious reasons…generate ‘pillows’ of assumptions…and are ineffective cushions against the sharp rocks of risk below’

Assumptions are like pillows – they are very comfortable and we are not aware of them for much of the time. The trouble is that our assumptions and the assumptions of other people that we are working with are likely to be different. When we don’t inspect our assumptions, we can overlook risks – so that is why our assumptions are like pillows.

It can feel like a waste of effort to inspect our assumptions – there are ways of working them into a workshop facilitation plan – that’s the easiest one to address.

Another way is to be aware of the feeling that something is not quite right in a conversation. Once I was negotiating a contract and almost starting to argue with the other party about a particular point – both of us thought that the other one was being a bit unreasonable. After a short break, we took a moment to clarify what we were discussing and it turned out that we both agreed the point, but had been discussing quite different things before the short break.

The main risk that assumptions cause in projects is delay. If we find ways to highlight assumptions earlier we can save wasted effort in circular discussions, rework or duplication.

It’s better to see the sharp rocks of risk than to cover them with assumption pillows.

Have you ever tried to do a nice thing that went completely pear shaped ?

Have you ever said something that was taken out of context ?

These are the unforeseen consequences, that surround us every day of our lives. The basic fact is that every interaction is open to misinterpretation. Sounds absurd but I propose it’s painfully true. The fact no one can read your mind or understand precisely what you mean is founded in the variety of life experiences we all have. We all have a “mental rule book” that we inherit/adapt/devise as we live our lives, moulded by our experiences and more importantly, our interpretation and responses to them.

Management and the unintended and invisible consequences

We are a modern culture of goal driven and result focused beings, rushing towards completion. The result is that there is entry level and management and the erosion of the middle.

The loss of the middle

The rush to completion culture, that is modern life, results in an erosion of the middle. Think about it, there is a devaluing and almost loss reflected by the middle layers of our work place and lives. This doesn’t mean that the middle layers don’t exist anymore because they do and if anything there are more of them. What has happened is the middle has expanded all while an erosion of its substance/quality has occurred. The middle has become a waiting room with no intrinsic value, just a place on the way to somewhere else. We are all trying to be/get somewhere else and therefore are focused forward and not in the present. It’s like people who are so busy, thinking of the next thing say, that they actually aren’t listening. They are actually, just frantically scanning /searching for the next sound bite to hang their comments upon. This type of hollowness is symptomatic of the erosion of the middle. This layer has become what I call “fluff” taking up a lot of room but with no real substance. The term busy work, tends to be made for this middle layer. So why has this happened?

Apprentice easy to learn hard to master

I remember buying a backgammon set when I was very young which had an instruction booklet with it. The instructions/rules were rather simple but it ended with this statement “easy to learn but hard to master” this line always resonated with me because I was a moratore’s son and knew that most things are easy to learn but really hard to master. The mastery of a skilled task takes time, time to encounter all possibilities and time to develop responses and reactions to them.

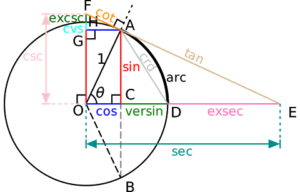

How many of us have learnt things, passed the exams and only years later, does the penny, actualy drop? Only then do we see for the first time what the concepts heart or the true nature of the knowledge was. Maths is littered with these sort of realisations, trigonometry is one.

I remember being told by a professor at university, when I was demonstrating and discussing with him how we learn and teach. He replied you only really learn something when you have to teach it, when you first learn anything, it is really just a getting to know you exercise, like a first date. This introduction allows you to pass an examine but really only superficially introduces you to the concepts involved. This initial exposure familiarises you with specific terms and basic concepts, so when you actually need to know and teach that lesson you can find the solution more easily and make it part of you.

The act of learning is greatly enhanced by teaching, why? The answer is simplicity itself. Everyone sees and exists in the world differently, these differences mean that when you learn something and try to understand it, you frame it in familiar and logical steps, for you anyway. When others try to learn and understand the same lesson they will also try to make sense of it according to their life view and understandings. So it’s obvious that when teaching you will find a continuum of how others perceive and try to understand the lesson. Some will think very much like yourself, others slightly differently and still others will need vastly different points of reference to come to terms with and understand the lesson. Good teachers must and can rephrase and explain things in a variety of ways, this necessity is what makes teaching the best way to learn because it stretches us to examine what we “know” from other perspectives and points of view.

The unforeseen consequence of teaching is you learn much more completely. This takes time and understanding.

So why do we rush to “completion” ?

Our modern culture is densely populated with 5 year plans, strategies, expectations, milestones and the list goes on and on. Every minute of every day in our lives is under constant scrutiny both internally and externally. We must develop and attain certain milestones within culturally expected time frames or we seem to be ineffectual or below the curve.

There is no room or time for mastery, we learn and we move on. The modern view is that “the now” is only a stepping stone to a future goal. The worth of the journey seems lost to us and only the allure of promotion and success is our goal. We have become tradesmen, with no patience or will to develop into master craftsmen. Society accepts the passable, to feed instant gratification and speed. The respect and value of craftsmanship and quality has become subservient to efficiency and greed. The attention span of the modern world is framed by sound bites and popularity poles.

Bread and Circus rule the day, with distractions and being seen as cutting edge, objectives in themselves.

Think about your workplace, how many times do we heard “they’ve been in that dead end job for years”, “they have no ambition” these statements maybe true but only partially so. The fact maybe that the worker derives get pleasure and satisfaction in developing their skills beyond acceptable and into the realm of mastery. Yet we don’t acknowledge this, we only see the same person in the same role, and evaluate this as “what is wrong with them?”

The absolute irony I noted while I was working IT, no matter how expert and skilled the programers were they were never “appreciated” as much as management. In fact it was sad to watch true masters of coding, having to become management so they could earn more money and get some appreciation. The actual engine which kept the company in business was devalued because they were content applying their craft. The ironic topper to this observation, was that graduates who had studied coding, just used coding to get a foot into a company, so they could quickly move into the management streams. Does the saying “too many Chiefs and not enough Indians”, spring to mind.

Words of wisdom from my father an old muratore “It takes hardly any extra effort to do a good job than a bad one.” This is very true, when you actually think about it, how much time, effort and money has been flushed down the toilet by bad projects with little or nothing to show for it?

The unforeseen consequence of our modern society is we rush to our goals and loose sight of the reasons and real benefits why we started in the first place.

There seems to be a disconnect between the limbs and the governing body, the brain. The “new talent” needs mentors to help and aid learning of best practises, while the “wiser” and older ones need the vitality of youth to physically accomplish the task and encourage new exploration into possibilities.

Companies are run like the military, chain of command, need to know and follow orders. They should be run as a biological system or organism, where there are feedback systems with more than one way to elicit change, the nervous system for rapid responses (management) and the endocrine system for slower invasive moderation (cultural).

The agile concept of self-organising teams can be mistaken as allowing the people within a team to do whatever they want to do – because eventually they will self-organise into an effective group. If I was told to be part of a self-organising team, my first reaction might be a feeling of freedom.

I could do whatever I thought was the right thing, such as, come into work at 3am and leave around lunchtime or write all my documents in Latin (because that would be fun and precise – although I would need to seriously brush up on my high-school Latin – I can only remember ‘canis in mensa stat’).

I was trying to think of a list of things that I could do by myself and ran out of them very quickly – we rely on other people at work to get our jobs done. With the two (silly) examples above, my sense of freedom would place a burden on others – not many people would be happy to attend my 3am meetings and very few would be able to read my Latin documents.

Another misinterpretation of self-organising might be ‘without constraints’ – which sounds wonderful, and could end up with similar issues. Constraint can mean prevention or it can be a thing that helps to shape our thoughts and actions in useful ways.

Back to the concept of self-organising teams. Teams cannot work in complete isolation, even in a small company there are other people involved. Imagine running a sandwich shop. Our Customers are likely to buy sandwiches during lunchtime – so we have a constraint of peak sales likely between midday and 1:30pm. We can only afford a certain amount of counter space, staff and supplies – and each fresh sandwich takes a minimum time to prepare, wrap and conclude the sales transaction. We can think of the shop as having inputs of fresh sandwich ingredients and outputs of sandwiches to happy Customers. The way that the shop runs needs to consider the inputs and outputs and then come up with the best way to get flow happening.

Now we are very far away from the concept of freedom and without constraints – we are tied to the shop for the long hours of work to service Customers for 90 minutes a day (and a few sales before and after that if we are smart). And yet, many people think of freedom as running their own business – how can we resolve this seeming paradox?

Now we are very far away from the concept of freedom and without constraints – we are tied to the shop for the long hours of work to service Customers for 90 minutes a day (and a few sales before and after that if we are smart). And yet, many people think of freedom as running their own business – how can we resolve this seeming paradox?

Perhaps freedom comes from the serving of others and is enabled by our reliance on others and we need to consider this in our teamwork. An effective self-organising team cannot be a bunch of people doing random stuff and magically becoming organised. The group needs to consider the inputs to the team and the outputs expected from the team – as well as the inputs and outputs for all of the work within the team. By observing these inputs and outputs and the way the work flows, we can improve over time.

In the sandwich shop example, we can place the ingredients in consistent places and monitor them as they empty during the busy periods. We need to discuss our observations about the effectiveness of that layout and any processes for topping up the ingredients.

Only by working together to share observations and ideas for improvement will we see any changes.

There was a great lunch place near my office that changed hands a few years ago and changed from quick service into very slow service almost overnight. I persisted for a while, but it did not get any better and I always wondered why the old owners did a much better job and these ones were inefficient. Now that I am writing this post, I think that the people in the lunch place were too polite with each other and tried to share the work – there would be 3 people making my sandwich, when before there was only one – or 2 at the most if they were not busy. The new owners divided the work up so that one person would prepare the bread and another 2 prepare the other ingredients – but not like a production line and they would be working over each other and slowing each other down. I imagine that this would have been frustrating for them and perhaps they did not discuss these little frustrations and observations, so the opportunities for small improvements were missed. I stopped buying my lunch from that place and there is a completely different lunch place there now.

Perhaps it would be useful to rename the idea of self-organising teams because it causes a lot of confusion. I would like to see teams that practice continuous improvement aiming towards great flow and the creation of value. Teams that are observant of the flow of the work from start to delivery as well as within the team and considerate of the impacts to others within and outside of the team.

Considerate-Observant Teams – the freedom to create value… and recognition of our reliance on others in order to be free.

IT Operations – the engine room of our organisations and seen as an unglamorous workplace area.

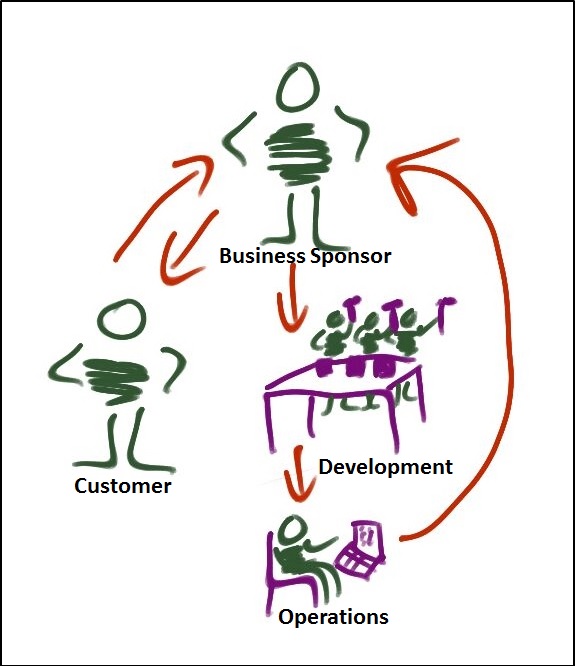

When we picture a software development lifecycle, we often picture it like this…

A business sponsor has an idea or identifies a Customer need, they ask the software development teams to build it and then it gets implemented into the production environment so that the business area can serve better experiences to our Customers.

A business sponsor has an idea or identifies a Customer need, they ask the software development teams to build it and then it gets implemented into the production environment so that the business area can serve better experiences to our Customers.

In this picture, the operations teams are seen as being far away from the Customers and treated as a ‘back of house’ function.

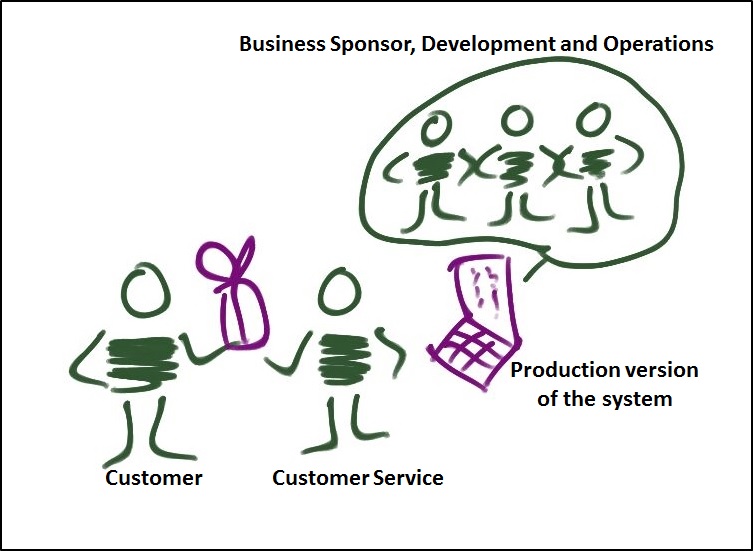

But there is another way to look at this picture.

In this one, the only way that our Customers can receive any value is from the operational (production) version of our systems. The operations teams are much closer to our Customers as it is their role to ensure that the production version of the systems are resilient and stable.

In this one, the only way that our Customers can receive any value is from the operational (production) version of our systems. The operations teams are much closer to our Customers as it is their role to ensure that the production version of the systems are resilient and stable.

If we use this second way of looking at the software delivery process, the needs of our Customers are pulling the delivery of value into the operational environment. In order for that value to get there, the teams from operations, development and the business sponsor areas all need to work together. This goes to the heart of what DevOps means to me.

For those of you who have spent some time doing operational roles, the following will be obvious – for others, if you get a chance to spend some time in the operations department, please do – it will provide many insights.

I once worked with a team where the developers and the operations people were co-located and we changed our development processes to consider the impacts to the operations team right from the start of design. We called it Minimal Operation Intervention and below are some examples of this principle.

In summary, our operational/production environment is the only one that we can deliver value from – all other activities in the development process need to focus on making the production environment resilient and a seamless experience for our Customers, Users and Operators.

Thank you again to Torbjörn Gyllebring and Steve for the conversations inspiring this post – any quality or factual defects are all my own however.

Thank you to Torbjörn Gyllebring and Thom Leggett for the conversations and inspiration to write this post.

It can be useful to step back from our work and study the decisions that we are making. Here are some of the ways to study decisions and how we can start to visualise the information.

Start by writing out the decisions and laying them out in a logical sequence – grouping similar ones together and consequential ones after each other. Draw some arrows between them – it can be helpful if another person is working with you to help clarify which decisions lead to others and their inter-relationships.

Sometimes there are loops such as the ones labelled ‘A’ and ‘B’ where, when we make decsion A, it changes how we should make decsion B which then impacts how we should make decision A. It might be possible that we get false ‘loops’ as well as the real ones when we are not clear about the decisions that we are making.

Once a decision has been identified, we start seeking the information required in order to make the decision. It is as if the decision is ‘pulling’ the information into it, and once there is enough, we can then make the decision. We can visualise this by writing the decision as a question on the top of a card and the information items required as bullet points under the question.

Some information items are actually prior decisions, we can use a code to link these cards together and put them up on a wall to show the realtionships. This allows us to have good conversations about both the activities required to gather information and the progress of the decisions that we are making.

Ideally, a group put together from different areas would all be working on the same thing at any one time and towards the same goal. Often this is achieved in agile teams and works well.

Sometimes, there are other reasons to pull people together from different areas to work on several goals at once. Here is a way to get an idea about effective ways for groups like this to work together.

Examples of Goals

Examples of GoalsAsk the group to state their goals – in the example, the three goals are

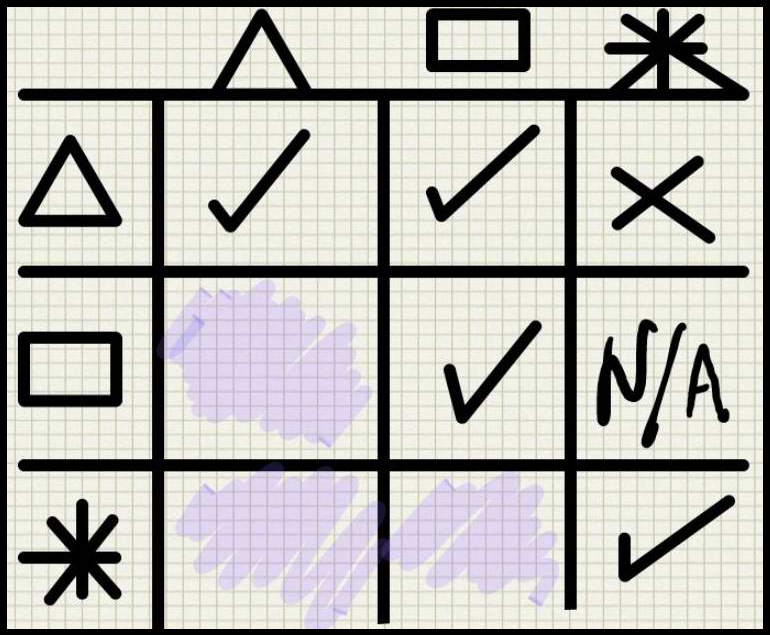

Put each goal across a page and also repeated down the left side – then ask for each pair of goals whether they align, conflict or are unconnected.

Goals Map

Goals MapIn this example

If we had a group put together with a goal map like this, we would need have discussions about the conflict and dependency so that we could work out the best way to start working together. In fact, we might ask why the people with the ‘destroy pyramids’ goal had been sent to this group in the first place.

I have been wondering about the similarities and differences between software development and large building projects.

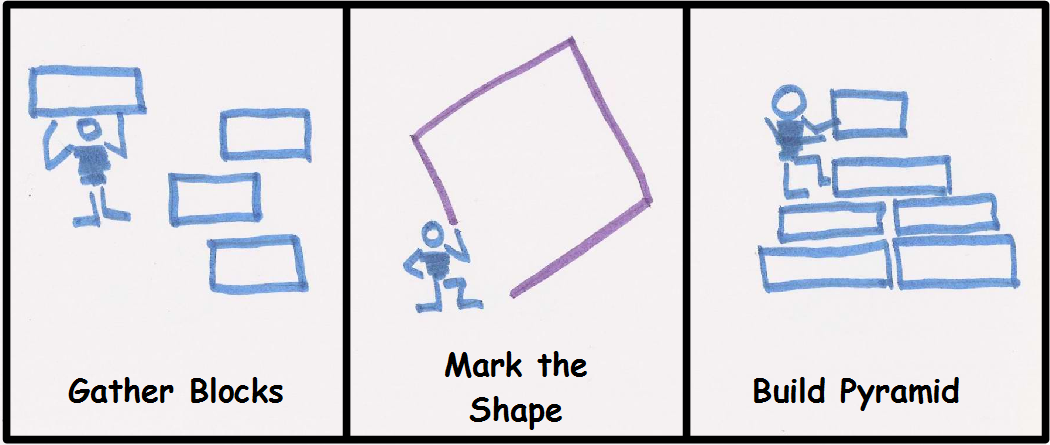

Building a Pyramid

Building a PyramidTake the example of building a pyramid. We firstly gather some blocks, then mark out the shape and then place the blocks in the correct places to build the structure. Tasks need to happen in a certain order, we cannot place the blocks before we have gathered them.

If we are developing in a green-fields environment, which features we build first does not matter very much. We can use customer value and learning opportunities to determine the first features. So it is less similar to a large building project.

If we are developing in a brown-fields environment, then we often need to consider existing systems and features that our customers are already using. These factors may constrain the order that we can develop and deploy new features. So this is more similar to a large building project.

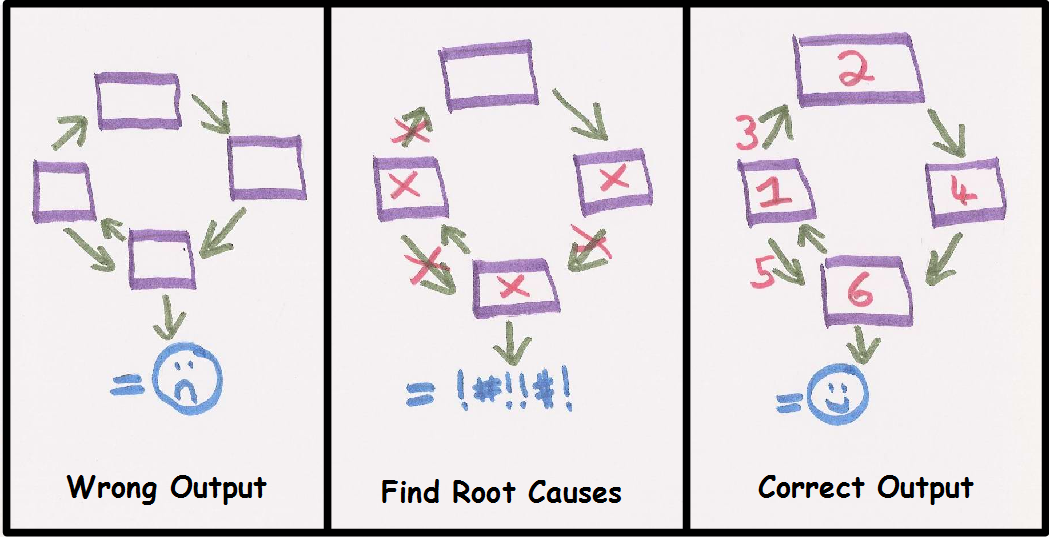

Consider the similarity between fixing a complicated system defect and brown-fields development. The order of developing and deploying fixes is extremely important to avoid causing further issues and rework.

Fixing Complicated Defects

Fixing Complicated DefectsIn the above example there are four boxes representing applications and five interfaces. Root cause analysis shows defects in three applications and three interfaces. The correct output can be restored when the six fixes are applied in the correct order.