The human ability to learn, take facts and abstract, invent and then innovate is very impressive. All these possibilities and then more so. We live in a world of information abundance, we google, we search and we condense, all with the goal to assimilate knowledge and be able to function.

The sheer amount of data, facts, ideas and interpretations of data, available to any of us, has had a profound impact upon the way we all function and behave in our day to day lives. The ‘data explosion’ impact ranges from work, socially, ‘family and friend’ and even our own development and the way we see ourselves.

Think about it, the amount of stuff we are exposed to is increasing every year, books added to the web, new research, new facts, new ideas, new concepts etc. etc… The human animal is a marvel but to cope with an inundation of information we fall back on the tried and true method of filtering the incoming data to make sense of it. We all do it and some better than others. The very process of filtering means we, collate, prioritise, group and rapidly make evaluations upon the various pieces of information bombarding our senses. The mind grasps at straws and we often jump to rapid conclusions and interpret the apparent facts according to our own experiences and world view. This is a very efficient way to process information and to be able to make informed decisions. So what’s the problem with this system of behaviour?

Now to answer this, allow me to briefly cover optical illusions.

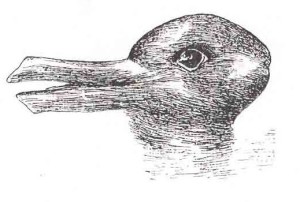

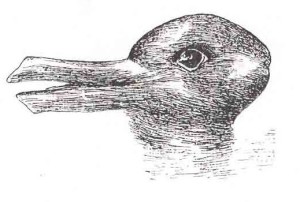

The classic examples of the brain being fooled by optical illusion such as the rabbit/duck illusion,

are testimony that we all do it. In an effort to make sense we rapidly jump to conclusions, very handy when trying to pattern match. Evolutionarily speaking one of our greatest abilities.

Wikipedia defines an optical illusion (or visual illusion) as being characterised by visually perceived images that differ from objective reality. Information gathered by the eye is processed in the brain to give a perception that does not tally with a physical reality of the source.

There are three main types:

1) Literal optical illusions create images that are different from the objects that make them,

2) Physiological illusions that are the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific type (brightness, colour, size, position, tilt, movement), and

3) Cognitive illusions, the result of unconscious inferences. The brain trying to understand perceives the object based on prior knowledge or assumptions (‘fills in the gaps’).

Pathological visual illusions arise from a pathological exaggeration in physiological visual perception mechanisms causing the aforementioned types of illusions. A pathological visual illusion is a distortion of a real external stimulus and are often diffuse and persistent.

Physiological illusions, such as the afterimages following bright lights, or adapting stimuli of excessively longer alternating patterns (contingent perceptual aftereffect), are presumed to be the effects on the eyes or brain of excessive stimulation or interaction with contextual or competing stimuli of a specific type—brightness, colour, position, tilt, size, movement, etc.

Optical illusions are often classified into categories including the physical and the cognitive or perceptual, and contrasted with optical hallucinations.

Of all the optical illusions, the ones I wish to focus on here are the cognitive illusions.

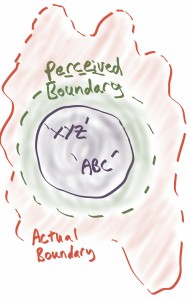

Cognitive illusions are assumed to arise by interaction with assumptions about the world, leading to “unconscious inferences”, an idea first suggested in the 19th century by the German physicist and physician Hermann Helmholtz. Cognitive illusions are commonly divided into ambiguous illusions, distorting illusions, paradox illusions, or fiction illusions.

1. Ambiguous illusions are pictures or objects that elicit a perceptual “switch” between the alternative interpretations. The Necker cube is a well-known example; another instance is the Rubin vase.

2. Distorting or geometrical optical illusions are characterised by distortions of size, length, position or curvature. A striking example is the Café Wall illusion. Other examples are the famous Muller-Lyer illusion and Ponzo illusion.

3. Paradox illusions are generated by objects that are paradoxical or impossible, such as the Penrose triangle or impossible staircase seen, for example, in M.C Escher’s Ascending and Descending and Waterfall. The triangle is an illusion dependent on a cognitive misunderstanding that adjacent edges must join.

4. Fictions are when a figure is perceived even though it is not in the stimulus.

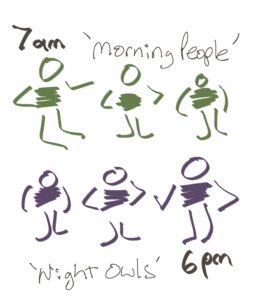

Now allow me to put forward the idea that as we become increasingly time poor and information burdened we increasingly begin to filter, even to the stage that we become unaware of it. This is where it can get dangerous.

I’m not talking about optical illusions jumping up at you in the workplace or in your day to day lives but I am talking about the way we all reduce information and events into “byte” sized pieces. Think about it, we dot point things, prioritise, we use jargon and, my pet hate, we make up acronyms. All in the name of efficiency and understanding. We have become a sound bite culture in an attempt to make sense and deal with all this stuff.

So what’s the problem? Well the reduction and filtering is. Think about it, reducing something means leaving something out or changing the original to a more compact form. Filtering means to sort something and then to determine what’s most important and then effectively ignoring other things to varying degrees.

When I was working in a laboratory I was told the story of a technique which was written up in a scientific journal. The Professor in our lab was trying to repeat the described technique and tried repeatedly, only resulting in failure. He followed the outlined procedure to the letter but to no avail. He ended up deciding to ring the parties concerned and found out that they had actually written in their original paper, that after a certain step in the process, they had gone to lunch for 2 hours. The scientific journal thought that this was not needed and removed this notation from the final publication. The irony was that without the 2 hour pause in the procedure the technique didn’t work at all.

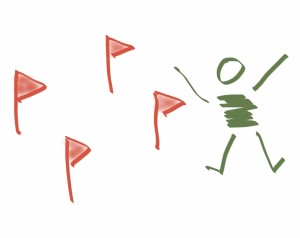

Sound bites can be just as dangerous because often you don’t know what has been filtered out and things can be taken out of context.

To highlight just how misleading sound bites can be, consider an ecological study conducted by a friend of mine. He was collecting data on the kangaroo densities in a particular area and some of the variables which he looked at included vegetation type, terrain, lightning strikes etc. Now when he processed the data statistically there was a very strong positive correlation between the number of kangaroos and the number of lightning strikes. We joked that kangaroos obviously sprung up from lightning strikes; ridiculous but supported by the statistics. The real reason was that lightning strikes meant that a tree was burnt or a fire started. This meant that the native vegetation sprouted regrowth, which was tender and plentiful attracting the kangaroos into the area. So without the extra information about fire and Australian ecosystems the data could be misinterpreted.

I propose that in the course of dealing with an influx of information by reducing it to dot points, catch phrases and sound bites, we can filter things to the extent that their true nature can be lost.

I also think that this culture of sound bites can lead to ambiguity, distortion, paradox and even fiction, like cognitive optical illusions.

So next time, you’re making sense of information or trying to convey and teach, remember to check if any of these are possible :

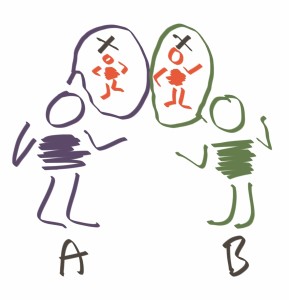

1. Ambiguity – Can your abridged version have alternative interpretations or be perceived in more than one way?

2. Distortion – Are any parameters you’re touching upon, affected by how you choose to focus on them?

3. Paradox – Can your abridged version lead to a cognitive misunderstanding resulting in a paradoxical or impossible conclusion?

4. Fiction – Can your abridged version be perceived incorrectly?

So when you’re tempted to sound bite a concept or idea just remember Benny Hill “Never Assume because you make an Ass out of U and Me”.

Often clarity is aided by multiple perspectives (yes my sound bite).

Sound bites work because the brain is driven to define reality based on simple, familiar objects, it creates a ‘whole’ image from individual elements but this is also a potential problem. This is the reason taking them out of context can be very dangerous and some people do it on purpose to discredit valid concepts or people… a slippery slope.

Appendix

Three main types of optical illusions explained:

1) Literal optical illusions create images that are different from the objects that make them,

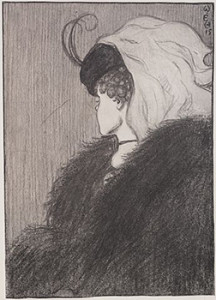

One of the most well-known literal illusions is the painting done by Charles Allan Gilbert titled All is Vanity. In this painting, a young girl sits in front of a mirror that appears to be a skull. There isn’t actually a skull there, however, the objects in the painting come together to create that effect.

2) Physiological illusions that are the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific type (brightness, colour, size, position, tilt, movement)

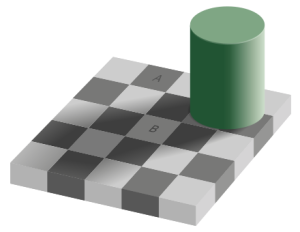

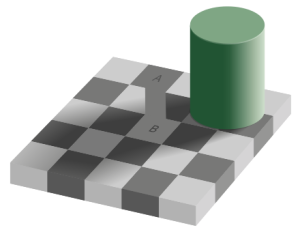

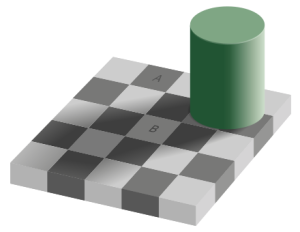

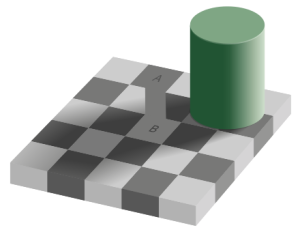

The checker shadow illusion. Although square A appears a darker shade of grey than square B, the two are exactly the same.

Drawing a connecting bar between the two squares breaks the illusion and shows that they are the same shade.

In this illusion we see square ‘A’ and ‘B’ as not the same colour, but when the image puts the two square next to each other; they do appear to be exactly the same colour.

3) Cognitive illusions, the result of unconscious inferences. The brain trying to understand perceives the object based on prior knowledge or assumptions (‘fills in the gaps’).

Cognitive Illusion Image – My Wife & My Mother-in-Law. Do you see a young woman or an old lady?

Wikipedia Optical_illusion

Study.com Lesson What are optical illusions; definition; types

Lecture-optical-illusion-perception

Wikipedia Sound_bite

There was an article about the ‘Tube Chat’ badges that caused controversy in London recently. The article explained that the cultural ‘norm’ on the London Tube is to not speak with strangers. In fact, that speaking with strangers on any train until well outside London is not normal.

There was an article about the ‘Tube Chat’ badges that caused controversy in London recently. The article explained that the cultural ‘norm’ on the London Tube is to not speak with strangers. In fact, that speaking with strangers on any train until well outside London is not normal.