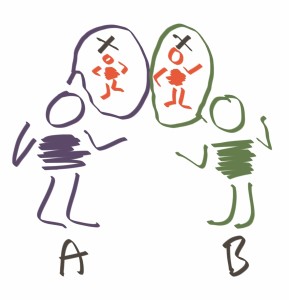

Imagine a discussion between managers.

Manager A – ‘How do think person X is performing?’

Manager B – ‘Doing a great job – understands what the need is and then delivers the outcome every time.’

Manager A – ‘Thanks – sounds good, I’ll count that as a ‘meets expectations’ in the review.’

Manager B – ‘Well, actually, I think that X exceeded my expectations – did you know that they have 5 years of delivery experience under their belt? I think that we are under-utilising X.’

Manager A – ‘Yeah – but they’re not really leadership material – I don’t think they will ever get above their current level in the company.’

Manager B – ‘That’s not their expectation – X has high potential, depth of experience and took this role to learn more about our part of the company. Have you had a discussion with X about their career goals and experience?’

Manager A – ‘Umm, Yes – but they don’t seem to be leadership material, I guess they will be disappointed…’

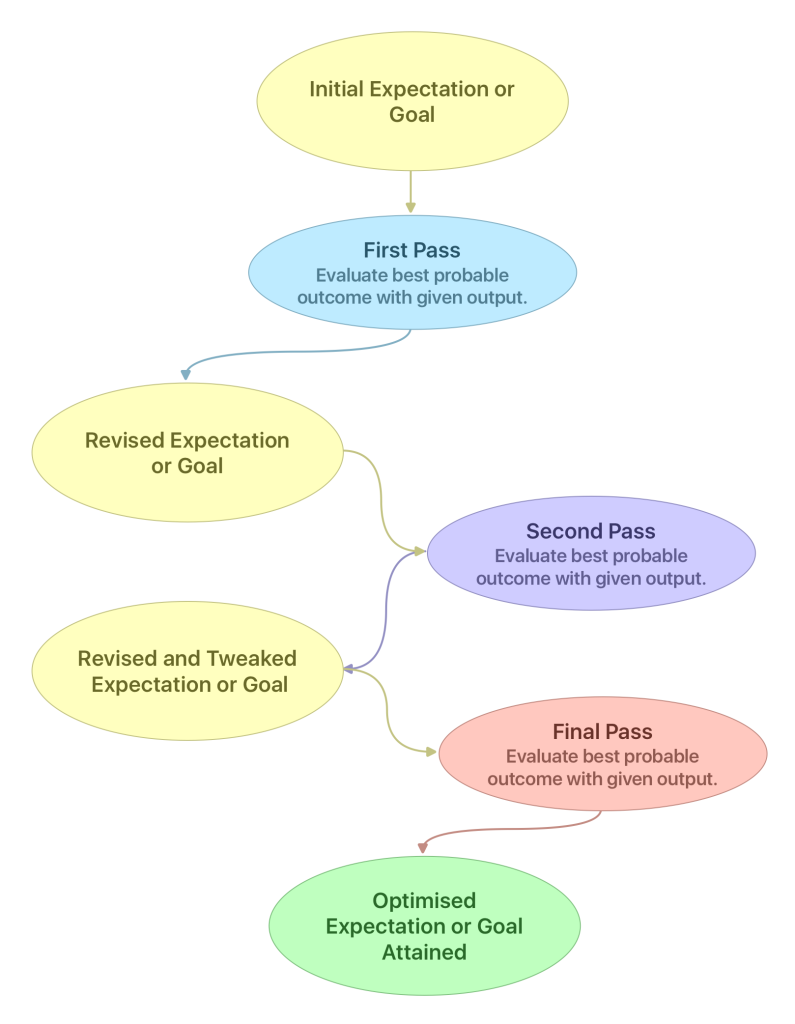

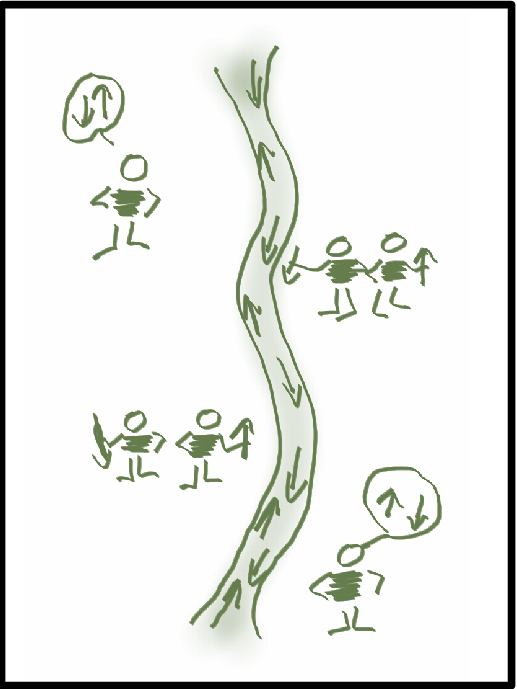

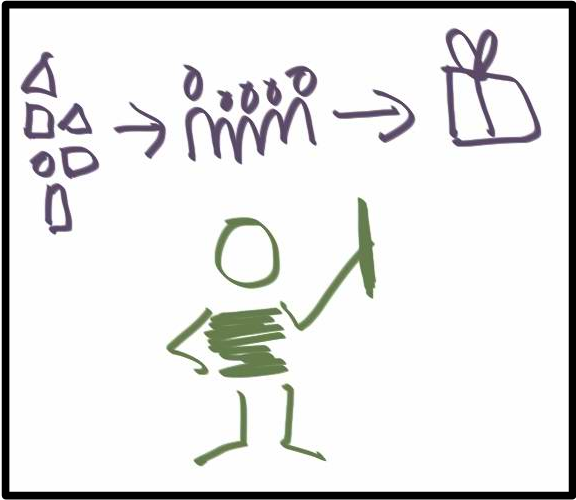

This imaginary conversation contains many examples of expectations – One manager has high and the other low expectations of person X and person X has high expectations of themselves. I believe that people are capable of living up to our high expectations and also of living down to our low expectations and whatever our expectations are, they will sense and comply.

This imaginary conversation contains many examples of expectations – One manager has high and the other low expectations of person X and person X has high expectations of themselves. I believe that people are capable of living up to our high expectations and also of living down to our low expectations and whatever our expectations are, they will sense and comply.

This is an important insight – our expectations are similar to assumptions and can be very tricky to surface. This means that they will become part of our subconscious and we are likely to transmit our expectations in ways that we cannot easily control such as body language, tone and our sentence construction.

So what can we do about it?

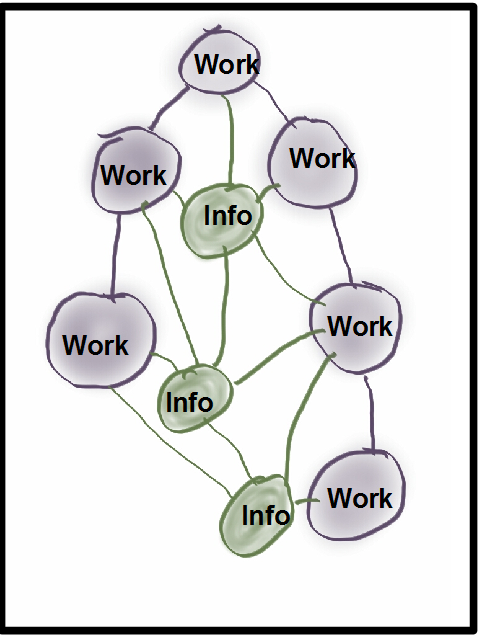

Any time we think that someone is doing an average or poor job, take a moment to reflect if it could be a bit of confirmation bias (that we always thought they were only capable of average or low quality and we have been selective in our observations to support this view). If this is the case, then imagine the best performer you have met and that this person has the potential to be just as great. Of course this applies in our non-workplace relationships as well – so we can get plenty of opportunities to reflect and practice in safe environments.

If we are not certain that a major factor is our own expectations, then find a couple of other people and sound them out about the person in question. Be very careful with this approach, because it is very easy for other people to pick up your expectations of others and answer in ways that will add to the confirmation bias.

In summary, expectations could be a major factor in productivity in the workplace – I wonder what would happen if everyone believed that their staff and colleagues were capable of achieving awesome instead of mediocre?