Tasks and activities are easy to manage – we see that a job needs to be done, schedule some time for it and then do it.

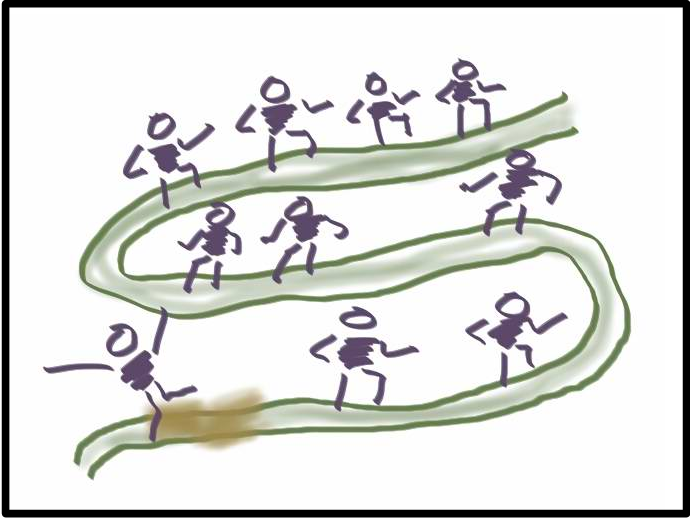

Queues are easy to see – waiting in line to pay for some goods when we go shopping – or waiting in line to see a popular tourist attraction. Waiting in queues like these is a good time to ponder about why the queue is there and how it could be better managed. Could the shop hire some more cashiers? Could the tourist venue allow more people through at once by setting out the attraction in a different way?

What about the queues that we cannot easily see such as those in our everyday work?

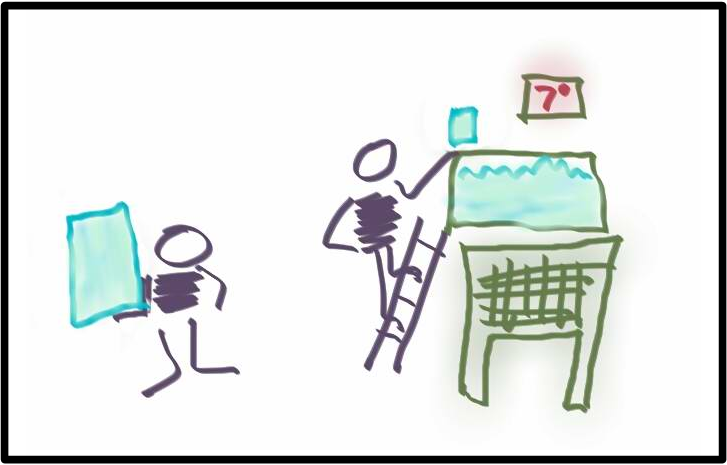

One thing that seems efficient is a regular set of decision-making meetings such as review and approval to proceed with an activity (like recruitment or a project). There could be a better way to manage these decisions – or are these regular meetings actually the most effective way to do it?

How many of us have rushed a presentation together to get it into the next cycle for a decision meeting? What might happen if the decision could be made as soon as we have brought together the information needed to make that decision? Would we have less of a sense of urgency and take longer to do simple things? Would it take less time because we know that the decision will be made as soon as we are ready for it?

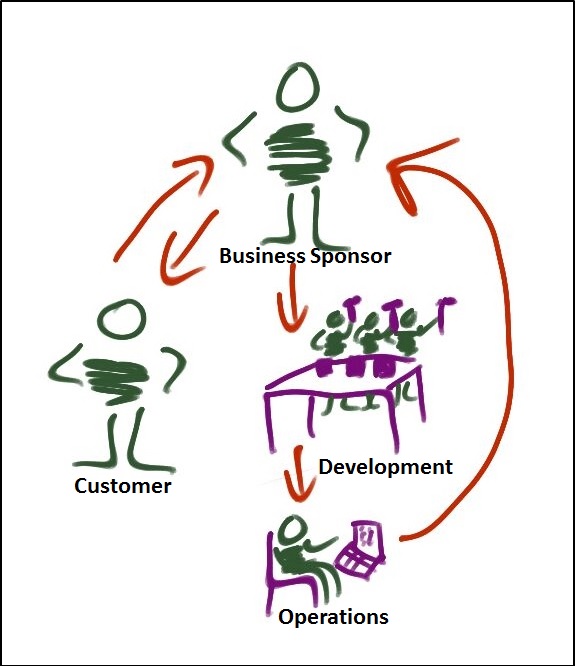

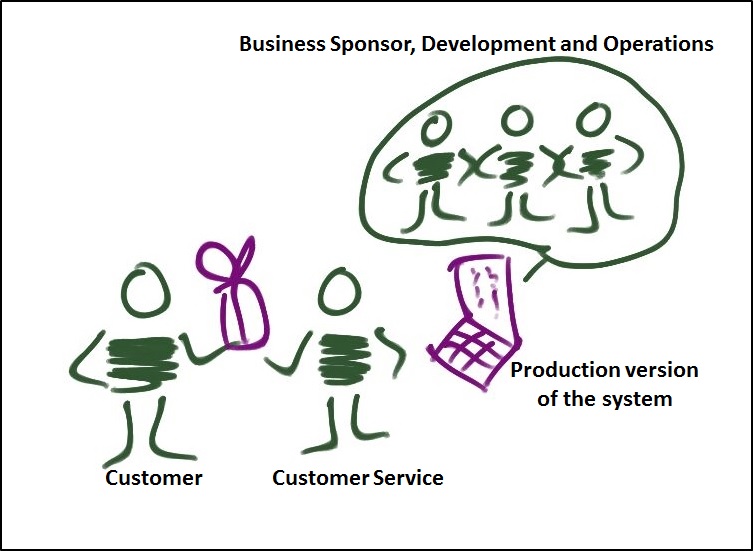

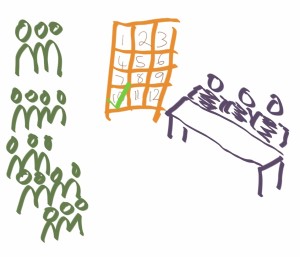

The decision to proceed or not is a constraint – up until that time, we are not certain that the project or other action will go ahead. By holding a regular meeting for the decision-making, we are making efficient use of the decision-makers time – but we are introducing queues into the process. Imagine that there will be 5 project ideas presented at the next meeting – all 5 have different sets of data that they need to gather in order for the proceed or not decision to be made. This data-gathering will have different lead times and each project will actually be ready for the go/no-go decision well before the meeting – so the length of wait-time in the queue will be different for each of them. How many of us record these wait times? Those things that remain invisible cannot be managed – people will be waiting on the decision-meeting before they can do the next set of useful actions. We could have 5 teams waiting on one meeting with senior decision-makers – because that is the best way to use the time of those decision-makers.

Constraint management is hard to do because it is very hard to notice the constraints. We get used to it taking a certain time to do things and waiting for the next decision point – because that’s how it’s done and it appears to be efficient.

Constraint management is hard to do because it is very hard to notice the constraints. We get used to it taking a certain time to do things and waiting for the next decision point – because that’s how it’s done and it appears to be efficient.

There are a lot of other constraints out there waiting to be noticed – the clues are there when our colleagues roll their eyes or complain about something. We can empathise with them and move on – or we can empathise and then dig a bit deeper.

- Is this a part of a pattern?

- Do other people also complain about it?

- How can we measure the things that people are complaining about?

- If we could measure them, what would we expect the measurements to be in order to validate or invalidate those complaints?

- If we are not already capturing the data, why?

Next time you are planning work – notice if you are planning activities, tasks or constraint management. Planning some time each week for observation sounds like a good idea – only by looking at something for a while and reflecting will we find ways to improve.