I like efficiency – when I walk into a shop, I want the sales person to help me find what I’m after and process the sale in a business-like manner. I also like to be treated as a person.

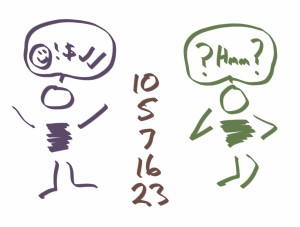

The other day, I was getting an ID card and the person serving me took a little extra time to find out about my transport means to the site. She then let me know about an extra public transport service that I wasn’t aware about. This is now saving me 10 minutes travel time each way which is 20 minutes per day. So a little less efficiency in one transaction has resulted in ongoing efficiency for me on a weekly basis.

When is efficiency good and when is it bad? It’s related to the type of system we are in.

When is efficiency good and when is it bad? It’s related to the type of system we are in.

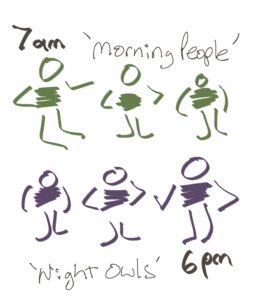

In the obvious domain on the Cynefin framework, we can attain best practice – repeatable processes. Here we can see the cause and effect relationships, observe bottlenecks and optimise the process to make it more efficient fairly easily.

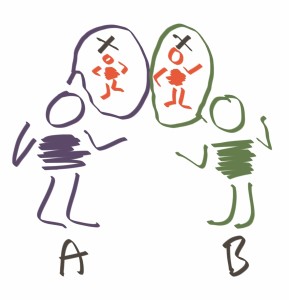

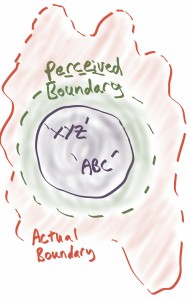

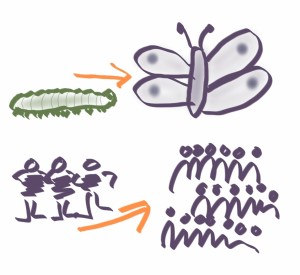

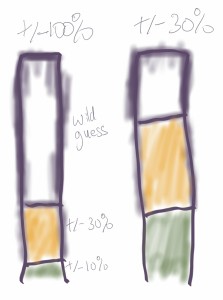

In the complex domain, efficiency is not easy – or is about something very different. Using my ID example, by having a little chit chat with me, the service centre person was able to identify an extra need that I had and supply me with valuable information. The efficiency in that exchange was the use of ‘anticipatory awareness’ – being sensitive to the hints in conversation that could express a need. Great sales and service people are very good at this – if we asked them to document the process they use, it would not be easy. It would not be a step-by-step ‘recipe’ – instead it might be something like a multi-branching if/then/maybe flow chart thing. I’m certain that it would be adapted or added to after almost every interaction.

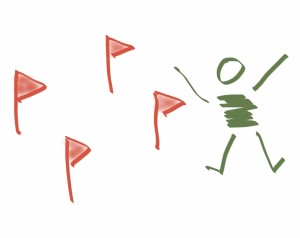

Another example of efficiency being bad is in farming, Imagine that we created plants that could extract all of the nutrients they needed from the soil and grow until the nutrients in that place were all taken up. This would be a disaster – we could only grow one crop in that space and it would desperately need all sorts of composts and fertilisers before it was useful again. If it can be that bad in a farming sense, perhaps we do not want all of our best practice processes to become super-efficient – it could deplete supplies in ways that we cannot anticipate.

In summary, efficiency can be good when we have processes that sit firmly in the obvious domain and can achieve standardisation and best practice (except if the efficiency leads to resource depletion). In these cases we can save time, money and effort by becoming more efficient. Efficiency can lead to poor outcomes if we try to apply it in the same way to the complex domain – this can waste time money and effort in the pursuit of gains that are not possible. Instead, here we want to sharpen our awareness and improve our methods of detecting small signals.