There was an article about the ‘Tube Chat’ badges that caused controversy in London recently. The article explained that the cultural ‘norm’ on the London Tube is to not speak with strangers. In fact, that speaking with strangers on any train until well outside London is not normal.

There was an article about the ‘Tube Chat’ badges that caused controversy in London recently. The article explained that the cultural ‘norm’ on the London Tube is to not speak with strangers. In fact, that speaking with strangers on any train until well outside London is not normal.

So I probably should not have started that long conversation with an American until we had left London and were well on our way to Edinburgh last month – oh well, lesson learned.

How do we discover the cultural ‘norms’ when we join a new group? These ‘norms’ are not something that can easily be explained – except for the extreme ones like dress codes. So we need to observe and deduce what the ‘norms’ might be. Do people have lunch at their desk? Do they go out of the office for coffee? …and so on.

Some are better at observation than others. Is there a way we can compensate for this diversity in observational skills? And why is this topic important?

It is important because the cultural ‘norms’ are what makes relationships easier – they remove friction and provide a level of certainty about how people will behave in various circumstances. If we want to shift behaviour to support improved ways of working, then we need to understand the current cultural ‘norms’. Then we need to work through how these cultural ‘norms’ are enabling or restricting good outcomes.

When we find a ‘norm’ that is restricting, it is tempting to call it out and just tell everyone to do something different.

I tried this a couple of weeks ago on my morning commute. There was a person sitting opposite me watching a soccer game on his phone without headphones. The sound was turned down, but I could clearly hear the ‘….and he scores blah blah blah…..the crowd goes wild….’ whistles blowing etc. It was really annoying. I assumed that he had blue-tooth earphones under his hood and that they might be faulty – he wouldn’t know – so I had better let him know. Because the cultural ‘norm’ on our trains is to keep your sound to yourself. I got his attention and said that I thought his earphones might be faulty because I could hear the sound. He barely looked at me and shook his head and then went on watching the game – he did turn the sound down a little.

I was a bit upset because he ignored me and did not seem to understand that others think it’s impolite not to use earphones.

A young lady then got on the train and sat in the seat next to him – doing her make-up in the selfie camera of her phone.

Years ago, etiquette guides were published to let people know what was socially acceptable. It was also common for people to let others know when they ‘crossed the line’ outside of the cultural ‘norm’ – but recently that is not acceptable. So the cultural ‘norm’ is to not say anything which means that we no longer have a consistent cultural ‘norm’ in society.

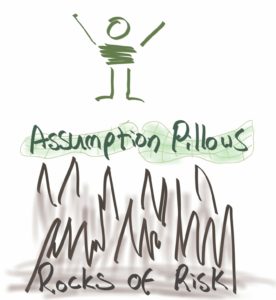

If this is true, then shifting behaviours in the workplace by direct methods is going to be almost impossible. Perhaps it is better to focus on more concrete things like processes and policies. These things are acceptable to make explicit and the cultural ‘norms’ will adapt around them. We should still monitor the cultural ‘norms’ in case they are leading to bad outcomes in our processes – but we should not try to change them directly.