Innovation is the current silver bullet to fix flagging businesses and help grow new ones – it’s leading to a lot of interest in ideas like Design Thinking.

Design Thinking starts with observing Customers and identifying their needs – rather than asking Customers what they want (or how they respond to key marketing phrases). Doing this well involves lots of research, taking copious notes and then combining these notes in many different ways to gain insights. It is from these insights that ideas such as the pedestals for front-load washing machines came about at Whirlpool – the video is a great one to watch to see Design Thinking principles in action.

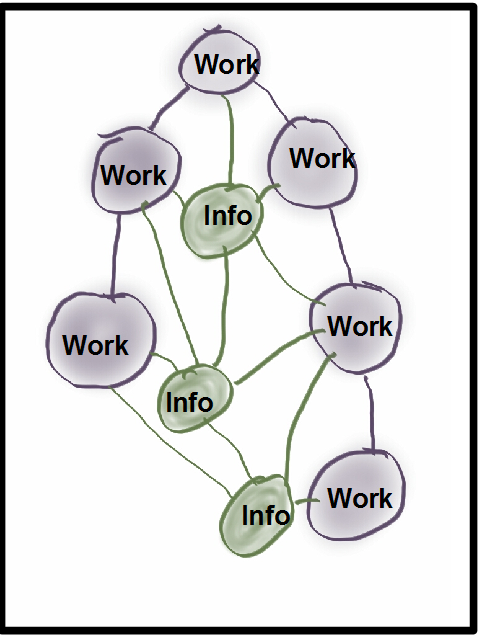

Done well, the research generates hundreds or thousands of notes – these might be stuck on a long wall and grouped together. It is key that different people do the groupings and that individuals walk away from the material for a while and then come back to it later. By doing this, the material is viewed in many different ways and the chances of finding novel ideas are increased.

How does this relate to serendipity in the workplace?

How many of us come into work at the same time each day, visit the same coffee place during our break and speak to the same people over lunch? With such regular habits, the chances of new ideas emerging are greatly reduced. It would be like one person taking all the observations from Customer research, classifying them and leaving it at that. The great ideas come from stepping away and then looking again with fresh eyes. Some of my favourite moments at work have occurred seemingly by chance – resulting in time saved for a project or a better way to design a solution.

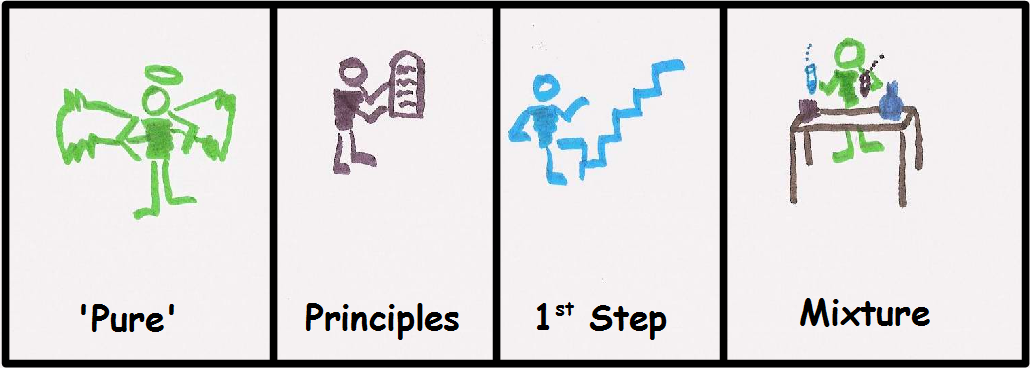

The entire premise of serendipity is that it is unlooked for good fortune – so we really shouldn’t try and force it to happen. We can enable it to happen more often by changing our routine, mixing with different people and speaking about different topics with the people we normally work with.

Try something different today…it might lead to a new idea.