The A-Ruminations team discuss knowing where to start, enabling constraints and metrics.

Category Archives: Systems

Activity vs Action.

In our modern world we are constantly expected to rush and frantically finish our tasks in the name of efficiency. Yet often we find that activity does not translate into the desired action or outcome. It is this “Rush to Action” which is the actual issue, often leading to poor outcomes and undesirable states of mind.

So why do we do it?

The basic fact is that we generally can not distinguish between activity and action. The realm of busywork is populated with people filled with a sense of accomplishment. The simple fact is we are driven by the evolutionary reflex of Fight or Flight. This predisposes us to rapidly respond by reaction, it is this proclivity to activity which makes us feel a sense of control when we are in activity. The difference between activity and action, is often only observed in the final outcome therefore it is very difficult for us and any onlooker to distinguish the two.

Doing things make us feel empowered and better; we feel in control and have a sense of fulfilment because we are doing something about it. Yet this activity is a hollow victory, if the end goals are not reached. The true reward is when we attain our objectives and goals.

If we take the real world example of Cave Diving, a highly technical and inherently dangerous activity, which happens to be fun and scary. Imagine you are diving in a sinkhole cave system and before you know it, you realise you’ve reached the bottom and have lost your bearings and the rest of your group. Initial instinct would be to begin searching for the others and this naturally becomes more frantic as time passes. Although this is a natural and understandable reaction, it usually is not the best course of action. This initial behaviour which manifests itself as activity, will often cause greater problems. The reason frantic activity in such a situation is not a good idea is that you will stir up any silt and mud off the bottom, this will muddy the water and reduce your visibility to the extent you can loose your orientation to the stage where you don’t even know which way is up.

Activity is not always the best action.

So in the above example reactionary activity is highly problematic but even in this example calmer heads and cool action will prevail. Surrounded by zero visibility, not knowing which way is up many would feel lost yet the fact that the bubbles you expire using SCUBA gear will always rise actually will help you identify which way is up. This simple fact and calm action can and will safe your life.

This predisposition to activity can and often does muddy the water when we are trying to determine the actions necessary to attain our goals. Running around like a headless chicken, is an apt description because we loose our senses in the frantic rush. We don’t see, don’t hear and can not clearly understand which are the best options, opportunities and course of actions.

How much Transparency?

The picture is an analogy about transparency – I want to see the person step out from behind the pillar – but I really do not want to see into them (their skeleton – or even worse, through their clothing). I’m also quite confident that other people do not want to expose such an extreme level of transparency.

So what is the ‘right’ level of transparency and why to we seek it?

I’m sitting in my lounge room and I can see out the window – it is a frictionless way for me to observe the front yard (through the transparent glass). If there was no window, I would need to go out the front door and walk around the corner to see the front yard – it requires effort and I would need to justify doing it.

At the risk of abusing the window analogy, perhaps what we mean by being transparent about things in the workplace is that we reduce the effort to find out and we also eliminate the need to justify why we want to know. It can be very useful and pleasant to observe things – we can feel happy seeing that the environment is as it should be – and we can take action when things are not ‘right’. If my cat starts to growl looking out the window – there is probably another cat in the front yard and I can choose to chase it away or not. If neither of us could see it (due to the lack of a transparent window in the wall), we would never have known the other cat was there and we would have lost the choice to act.

We need to be careful about where we seek transparency – I do not want my whole house to be made out of glass – and we have curtains over windows when we want privacy.

In the workplace, it would be great if we could see everything without any effort and justification – but it can feel very threatening. When we feel threatened, we want to protect ourselves – so reducing effort in one way (frictionless observation – transparency) can increase effort in another way (trying to close the curtains or cover up our skeletons).

Be careful what level of transparency we ask for – it can be a good thing, and just like other good things (such as water and oxygen), too much of it can cause damage.

Customer Experience and IT Operations

IT Operations – the engine room of our organisations and seen as an unglamorous workplace area.

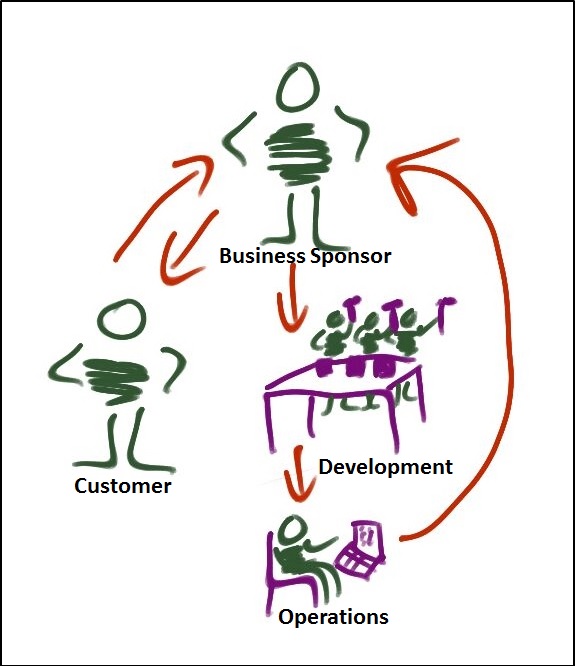

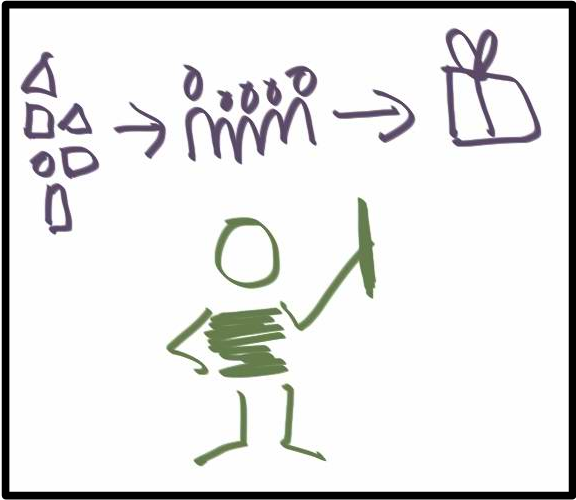

When we picture a software development lifecycle, we often picture it like this…

A business sponsor has an idea or identifies a Customer need, they ask the software development teams to build it and then it gets implemented into the production environment so that the business area can serve better experiences to our Customers.

A business sponsor has an idea or identifies a Customer need, they ask the software development teams to build it and then it gets implemented into the production environment so that the business area can serve better experiences to our Customers.

In this picture, the operations teams are seen as being far away from the Customers and treated as a ‘back of house’ function.

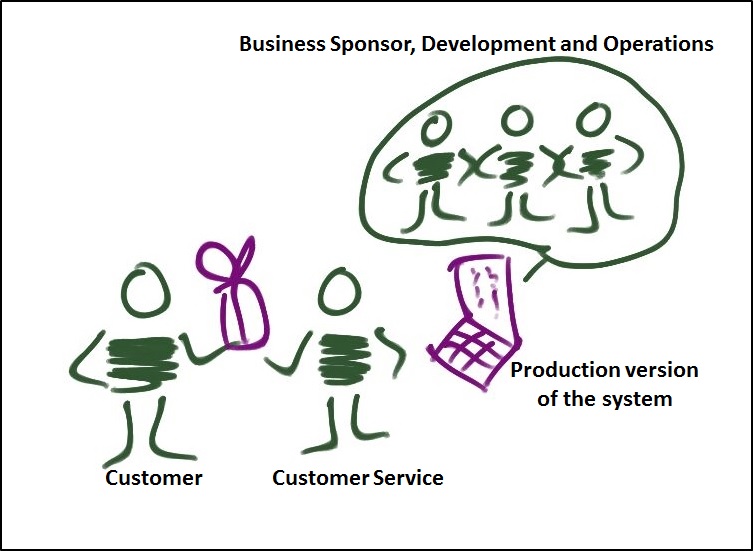

But there is another way to look at this picture.

In this one, the only way that our Customers can receive any value is from the operational (production) version of our systems. The operations teams are much closer to our Customers as it is their role to ensure that the production version of the systems are resilient and stable.

In this one, the only way that our Customers can receive any value is from the operational (production) version of our systems. The operations teams are much closer to our Customers as it is their role to ensure that the production version of the systems are resilient and stable.

If we use this second way of looking at the software delivery process, the needs of our Customers are pulling the delivery of value into the operational environment. In order for that value to get there, the teams from operations, development and the business sponsor areas all need to work together. This goes to the heart of what DevOps means to me.

For those of you who have spent some time doing operational roles, the following will be obvious – for others, if you get a chance to spend some time in the operations department, please do – it will provide many insights.

I once worked with a team where the developers and the operations people were co-located and we changed our development processes to consider the impacts to the operations team right from the start of design. We called it Minimal Operation Intervention and below are some examples of this principle.

- When we designed a batch process, instead of expecting the operations team to find out what was wrong and restart it manually, we would design in the ability for the batch process to detect common fault conditions and rollback/restart without operator intervention.

- There can be a temptation to save money and time during development by making some processes manual – this goes directly against the principle of minimal operational intervention. In my view, if our operations team members spend most of their time in the operations room just monitoring our systems and nothing else – that is good design built in.

- I’ve also heard of a case where development teams were doing the right thing by building alarms into their new features – but they never updated or retired pre-existing alarms. The operations team were left with a confusing array. We need to consider the experiences that we want our operators to have at the same time as we focus on the Customer experiences and value that we are delivering.

In summary, our operational/production environment is the only one that we can deliver value from – all other activities in the development process need to focus on making the production environment resilient and a seamless experience for our Customers, Users and Operators.

Thank you again to Torbjörn Gyllebring and Steve for the conversations inspiring this post – any quality or factual defects are all my own however.

Linear, Non-Linear, Predictable and Unpredictable

Firstly, a thank you to Torbjörn and Steve for the conversations and feedback leading to these thoughts. Torbjörn has also written a post on this theme for those who have not yet seen it.

We can have a tendency to use linear and predictable as synonyms, but there are non-linear concepts that are also predictable and one of them is called hysteresis.

The easiest example of hysteresis is a thermostat for a heater. If we use one temperature setting to turn it on and off, then it will click on and off endlessly. If we set the on temperature just a little under the desired one and the off temperature just a little over it, then it works much better. When we walk into the room and measure the temperature only, then we cannot know if the heater is currently on or not without knowing the historical temperature and thus whether the room is currently cooling down or heating up.

So this is an example of a predictable process that is non-linear – we can use mathematical modelling to generate that predictability. I wonder if there are other processes that are non-linear, but still have some predictability in our work places.

One example might be change initiatives. We start at one level of understanding, do some training, coaching, communications and other ways of influencing change. After a period of time we move up to a new level of understanding. Then as other things happen and new people join the group, we lose some of that understanding – but it is likely that we are still above the original level.

I’m still looking for other examples – but hypothetically, a whole bunch of non-linear processes over-lapping and intersecting with each other would likely look like a very complex system.

Of course, mathematically, we would then be able to demonstrate these parts of the system and their predictability – but that is not really the point. We are all observers of our world and how we experience it as individuals is different for each of us. Therefore, the natures of systems that we interact with will differ according to our experiences of them and what seems predictable to one person can appear quite random to another one.

Of course, mathematically, we would then be able to demonstrate these parts of the system and their predictability – but that is not really the point. We are all observers of our world and how we experience it as individuals is different for each of us. Therefore, the natures of systems that we interact with will differ according to our experiences of them and what seems predictable to one person can appear quite random to another one.

Back to the title of this post – along the gradient of predictability, we move from linear with obvious cause and effect to non-linear, such as hysteresis with less obvious correlation, then towards a lot less certainty where the relationships are dispositional and then to randomness. Most of the time whatever we are observing is likely to have a mixture of these attributes both inherently and from the ways that we experience it. Taking the example of a thermostat, I wonder how many other things also appear quite simple and are really elegantly complicated and on the flip side, how many things appear complex and are likely non-linear, but still predictable?

Types of Work

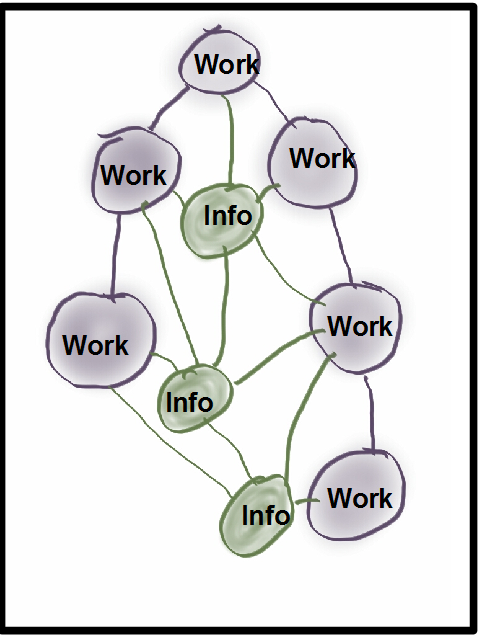

Following on from the earlier post about decisions, what would we do differently if we realised that we have been mixing together the concepts of creation work and information flow work?

This is the way we usually think about work – doing things, fixing things, reporting completion rates and then measuring the amount of value delivered. As we perform this work, reports get generated, decisions get made and dependencies managed.

Information is required to support decision making and also for the purposes of monitoring. We tend not to focus on this type of work. There may be an advantage to specifically calling it out.

- Groups that gather data to flow up to decision-makers – if there is clarity about what decisions are being made and what information is required in order to make them, then these groups could be more effective

- Groups that help disparate teams to work together – what decisions do the teams need to make or what types of data do the teams need to monitor for dependency, risk and issue management?

Perhaps our work structures would look more like the picture below.

Creation and Information Flow Work Intertwined

Creation and Information Flow Work Intertwined

Roles and teams specifically created as either primarily creation work or information flow work and then structured so that they intertwine. This could free up capacity in the creation work roles as they would not need to do so much reporting. It could also allow the information flow roles to better describe the value that they provide to the organisation in the support of decision-making, communications and monitoring.

Layers

I used to wonder why organisational charts were drawn with the executive roles at the top – instead of the other way around to show that the management layers support the operational ones to get work done. This support takes many forms.

I used to wonder why organisational charts were drawn with the executive roles at the top – instead of the other way around to show that the management layers support the operational ones to get work done. This support takes many forms.

- Control – Watching out for bad things and preventing them

- Assistance – Watching out for areas that are struggling and helping directly or arranging for help to be provided

- Decisions – Ensuring that information is flowing to and from teams so that decisions can be made – at whatever level is best for the decision to be made

The management function can also be described as similar to being a conductor – making sure that work is flowing in and out of a team smoothly and the team has the right skills and capacity to do the work.

The management function can also be described as similar to being a conductor – making sure that work is flowing in and out of a team smoothly and the team has the right skills and capacity to do the work.

I have been wondering what it could be like if we did not have management as a function any more.

- Everyone could be responsible for observing the system of work and making improvements whenever needed – in a continuous way.

- People could find their own valuable work to do – and just get on with doing it – this includes helping others when they need assistance.

There is a lot of value to be gained from having different views of data and information available. We currently cover this by having management layers – I wonder what we would call this function if we did not have management any more?

There is a lot of value to be gained from having different views of data and information available. We currently cover this by having management layers – I wonder what we would call this function if we did not have management any more?

Systems

What is a system?

One example is a circulatory system – with our heart at the centre.

Another example is a group of people – how they interact, their shared experiences and culture.

Another example is a group of people – how they interact, their shared experiences and culture.

So systems can be a grouping and how we look at groupings.

We can learn about systems in at least two different ways.

- We can look at each element in a system in order to understand how it works by adding together the knowledge we gain about each element.

- And we can look at the system as a whole and try to understand it as a whole.