The method for Multi-Hypothesis research that Jabe Bloom describes in his Failing Well session is very useful for exploring ideas and gaining new insights to problems.

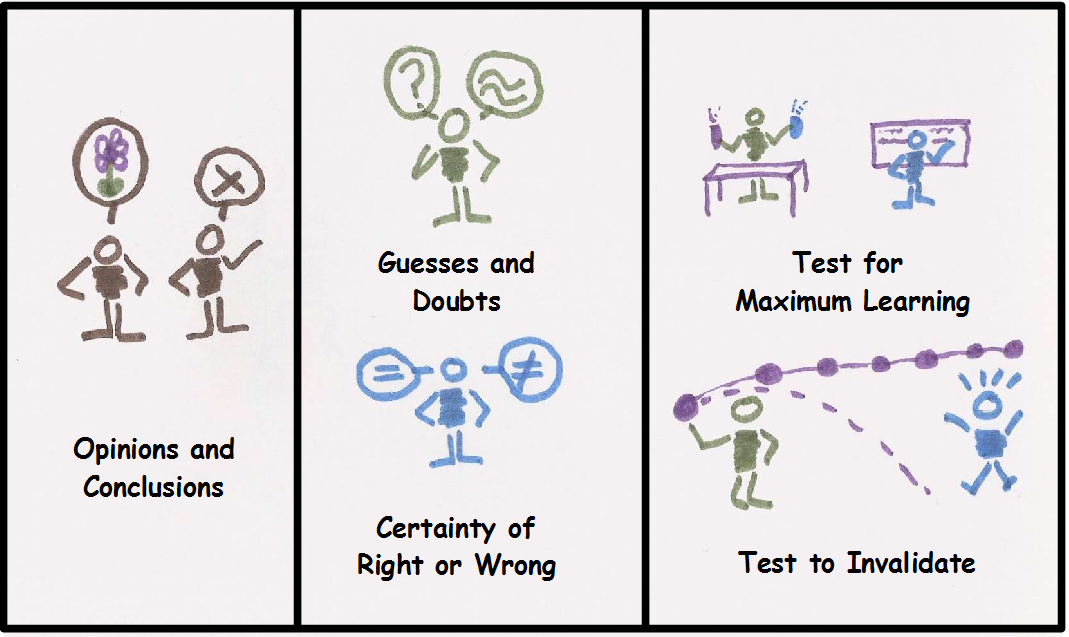

The main idea is to use ambiguity by presenting factual statements to a group and allowing each person to form their own opinions and conclusions about those facts.

Causal Chains

We ‘unpack’ what thoughts may have led to the original opinions and conclusions, some thoughts will be certainties that the facts are right or wrong and others will be guesses and doubts.

- Guesses and doubts are then explored to find ways that we can conduct tests or experiments in order to learn – the focus being on the smallest effort we can invest in order to learn something useful, regardless of the test failing or succeeding.

- Certainties are sometimes worth testing as well – in the picture above, we try to invalidate gravity by throwing a ball – if it did not fall, we would be surprised and have a great opportunity for learning.

This workshop method can be completed in as little as 60 minutes with a small group, 90 minutes is comfortable for a group of about 10 people. It is a great way to get a lot of ideas in a short time and to shed some biases in our thinking by allowing many different points of view.